File

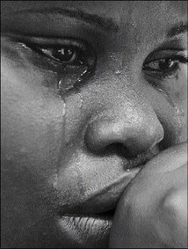

A mother is twisted in grief after a murder in Trench Town, west Kingston, on Thursday, March 29, 2007.

Tyrone Reid, Sunday Gleaner Reporter

WHEN MURDER appeared on the doorsteps of John Oldfield'shome, he was ripped to shreds.

Losing his only brother to gun violence, and the grief that followed was natural. But what consumed the young man weeks after he had laid his brother to rest was the longing for revenge.

Neither Oldfield nor his brother was a gang member, and Oldfield knew his brother and mentor was innocent. There was only one way out, he thought: find out who did the killing and "avenge my brother's death".

A wise word spoken by his mother prevented him from putting his plan into action. She told him she did not want to end up losing two sons.

Oldfield saw the bigger picture, did nothing, and today enjoys pride of place as the only male among five siblings in the household.

Like Oldfield, many persons, including law-abiding citizens, yearn for swift justice after a loved one is murdered, and in many instances, they look for this justice outside of the formal justice system.

This is not helped by the rate at which the Jamaica Constabulary Force solves murders.

Last year, the police reported that 22 per cent of the 1,611 reported murders had been "cleared up".

By "cleared up", the police do not mean that the killers were caught, arrested, tried and convicted. In many cases, the alleged killer was fatally shot by the police and the killing included among the list of those "cleared up".

Culture of revenge

In June last year, University of the West Indies psychiatrist, Jeffrey Walcott, argued that a lack of confidence in the justice system was chiefly responsible for the culture of revenge that had embedded itself in the country.

"The perception among most Jamaicans is that the police cannot be trusted, and when people feel they will not get redress through the legally established channels, they set up their own systems," Walcott said.

At that time, Assistant Commis-sioner of Police Glenmore Hinds, who heads the intelligence-driven unit, Operation Kingfish, told The Sunday Gleaner that "the thirst for instant revenge" and "an inability to resolve conflicts", were factors contributing to reprisal killings (classic examples of the timeless truth that 'hurting people hurt people').

Feeling the need to exact revenge is natural, says the Reverend Devon Dick, pastor of the Boulevard Baptist Church, who spearheaded a national forgiveness campaign in 2003.

But, despite the natural desire for revenge, Dick argues that the primal thirst for blood does not have to be appeased.

"It is to be understood that it is a natural reaction - to feel that if you don't seek revenge you are dishonouring the memory of the victim," reasoned Dick.

Relief and release

He explained further that when a loved one is murdered, the urge to exact revenge falsely promises some sort of relief and release. The man of the cloth added that after a revenge killing, many people feel justified.

When counselling, he believes it is important to affirm that the desire to seek revenge is a natural part of the emotions that unfolds in the wake of a murder.

However, the persons affected by the death of a family member or friend should be told that revenge killings "just continue a cycle of violence that does not help". And, that it is a sad sequence they should not want to perpetuate.

Additionally, people must be told, Dick said, that choosing not to take revenge does not mean that one is allowing the perpetrator to get away with murder.

Name changed upon request.

tyrone.reid@gleanerjm.com