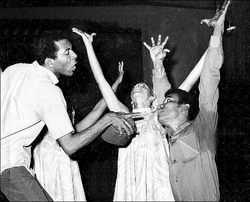

Seen here from left, are Trevor Rhone and Cheryl and Raymond Hill in the 1968 production 'Black Power' at The Barn Theatre.

Trevor Rhone of Beckford and Smith's High School (later renamed St Jago High School) was one of a handful of promising young male performing artistes who sometimes attended rehearsals in their school uniforms in the mid-to-late 1950s. Others included actors Winston Stona of Jamaica College, Percival Darby of Wolmer's Boys' School, Karl Binger of Calabar High, and dancer Garth Fagan of Excelsior High. They were talented, intelligent, disciplined and highly motivated.

In 1960, at the age of 20, Rhone made a success of the role of the middle-aged Elder Steele, one of the principal characters, in the premiere production of my Bedward play at the Ward Theatre. Shortly after, he entered the Rose Bruford School of Speech and Drama in Kent, England, where he was the top student when he earned a diploma in Speech and Drama.

Different places, opposite sides

As we were almost always in different places on opposite sides of the Atlantic for more than a decade, I had little further contact with Rhone until 1972 when, on a working trip back home, I saw his first big hit, Smile Orange, at The Barn. A couple of months later, Yvonne Brewster and I co-produced Smile Orange in London with her as director and me playing the role of Cyril, the bus boy. We took it on tour of 13 London boroughs with significant Jamaican/West Indian populations. It was a thrill working in a foreign land with such Jamaican theatre greats as Charles Hyatt and Mona (Chin) Hammond under Brewster's brilliant direction in a play to which we could all closely relate. Smile Orange resonated with the West Indians and also had considerable crossover appeal. It enjoyed very favourable reviews in local newspapers in the host communities and in the most prestigious British publication, The Times.

It was exciting and fulfilling to have a highly-skilled new Jamaican playwright at a time when we were woefully short of worthwhile Jamaican material for the stage. Rhone's work was never half-baked. He was the superb craftsman of our theatre. He faithfully followed Aristotle's dictum that "a play must have a beginning, a middle and an end".

He lived up to Mervyn Morris' definition of a writer as "one who rewrites". His ears were well tuned to dialogue, his characters were rounded, well-drawn and readily recognisable and character relationships credible. His plays were well layered and textured. They had suspense, interest and cumulative build both within scenes and from one scene to the next until the final resolution which was climactic and consistent with the promise of the plot. Above all, his writings accorded with the possibilities and limitations of our technology. One of his gifts to Jamaican theatre which has benefitted other writers and directors, including myself, was his division of even small stages into several locations so that scene changes were made simply by switching lights, thus avoiding the embarrassing old noisy, time-consuming and distracting changing around of scenery in the dark.

Four stage productions

As an actor, I appeared in four stage productions of Rhone's works - as the bus boy in Smile Orange and Russ Dacres in School's Out, both directed by Brewster; the police superintendent in Pepper, directed by Carol Lawes; and Joe in a second production of School's Out, directed by Rhone himself. I also played the role of Norman Manley in an audio biography that Rhone wrote, produced by Brewster, to mark the centenary of the National Hero's birth in 1993.

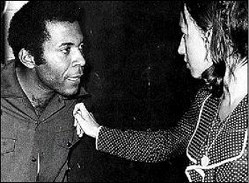

FOR THE BARN: Trevor Rhone and Johanna Hart are seen in rehearsal for 'The Collection', a play by Harold Pinter, which was produced for Theatre 77 and opened at The Barn, Oxford Road, on Tuesday, April 14, 1970.

- File photos

Rhone and I shared the writing of the skits and songs that comprised the revue One Stop, Driver, which he also directed. He was as meticulous in his directing as he was in his writing. He neither spoon-fed his actors nor dictated to them, but methodically helped them to find their characters. I attributed to his perfectionism a statement he repeatedly made that one had to listen only to 30 seconds of a play in performance to know if it was any good.

He was a very shrewd businessman and an extraordinarily good marketer of his skills and his works. The highly successful run of One Stop, Driver was interrupted by Hurricane Gilbert. At the first warning, anticipating the worst, he suggested that we immediately start writing post-Gilbert material and go into rehearsal as soon as possible to be ready to resume without delay when the power returned. And so it was.

His conversation was often flavoured with theatrical metaphor. For him, the first half of Gilbert was Act One, the second half Act Two and the period of calm as the eye passed was the intermission. Having now taken his final bow, Trevor Rhone richly deserves a standing ovation.